Airplanes and Tales.

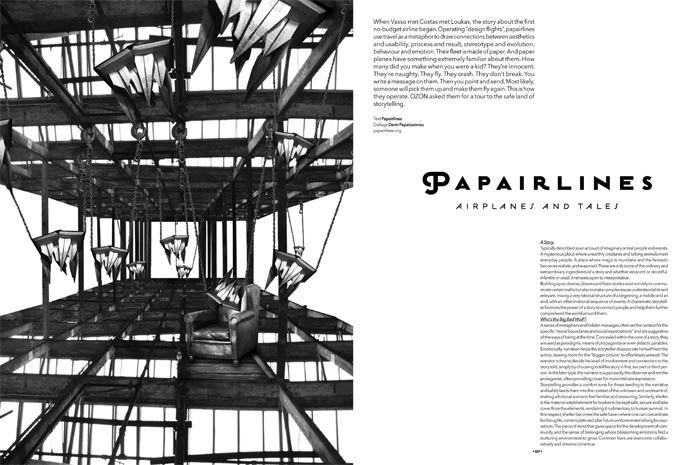

When Vasso met Costas met Loukas, the story about the first no-budget airline began. Operating “design flights”, papairlines use travel as a metaphor to draw connections between aesthetics and usability, process and result, stereotype and evolution, behaviour and emotion. Our fleet is made of paper. And paper planes have something extremely familiar about them. How many did you make when you were a kid? They’re innocent. They’re naughty. They fly. They crash. They don’t brake. You write a message on them. Then you point and send. Most likely, someone will pick them up and make them fly again. This is how we operate.

A Story.

Typically described as an account of imaginary or real people and events.

A mysterious place where unearthly creatures and talking animals meet everyday people. A place where magic is mundane and the fantastic becomes realistic and reasoned. These are only some of the ordinary and extraordinary ingredients of a story and whether innocent or deceitful, infantile or cruel, it remains open to interpretation.

Building upon desires, dreams and fears stories exist not only to communicate certain truths but also to make complex issues understandable and relevant, mixing a very rational structure of a beginning, a middle and an end, with an often irrational sequence of events. A charismatic storyteller borrows the power of a story to connect people and help them further comprehend the world around them.

Who’s the Big Bad Wolf?

A series of metaphors and hidden messages often set the context for the specific “moral boundaries and social expectations” and are suggestive of the ways of being at the time. Concealed within the core of a story, they are used as paradigms, means of propaganda or even didactic parables.

Emotionally, narration helps the storyteller disassociate himself from the action, leaving room for the “bigger picture” to effortlessly unravel. The narrator is free to decide his level of involvement and connection to the story told, simply by choosing to tell his story in first, second or third person. In the later type, the narrator is supposedly the observer and not the protagonist, often providing cover for more intimate expression.

Storytelling provides a comfort zone for those tending to the narrative and safely lands them into the context of the unknown and undreamt of, making a fictional scenario feel familiar and reassuring. Similarly, shelter is the material establishment for bodies to be kept safe, secure and take cover from the elements, rendering it rudimentary to human survival. In this respect, shelter becomes the safe haven where one can concentrate his thoughts, contemplate and plan future ventures materialising his aspirations. The peace of mind that gives space for the development of community and the sense of belonging where blossoming emotions find a nurturing environment to grow. Common fears are overcome collaboratively and dreams come true.

Are we there yet?

Storytelling becomes a starting point for imagining and creating a future of hope and optimism, allowing the mind to travel in time and space. Remember all those early SciFi novels and films featuring flying cars on the turn of the century? Well even if cars still don’t fly, they draw a great amount of knowledge from aviation technology, be it composite materials, global positioning systems or more; let alone the experiments that eliminate the driver.

As the example suggests, the value of stories and storytelling extends beyond acting as a compass for the future to becoming a point of reference one can fall back to and measure the distance between reality and the once projected scenario. Subsequently stories become the common ground for a community to assess its direction and achievements, examining whether it has remained true to its original beliefs and values.

After all, just like shelter, a story is a crafted intellectual sanctuary of fantasy and imagination that allows aspirations to flourish.

But is storytelling just a linguistic tool that demonstrates the power of words in shaping the imagination, or is the world we live in an ever-changing visual narrative that we subconsciously consume through pictorial representations and symbolism? Storytelling and design share a long and intimate history. Storytelling provides the grounds for design to happen whereas design fills in the gaps that complete a story. Isn’t the look and feel of a book integral to the experience of reading it? In an attempt to explain design through an etymological approach, Vilém Flusser draws connections between definitions such as plot and scheme, describing the designer as “a cunning plotter laying his traps”. Plot is the way a writer, director or storyteller devises the sequence of events in his story, being the vital part in a novel, movie or any form of narration. The designer becomes a storyteller through the way he explores, unfolds and moves the plot forward, from an idea to something with material status, in order to create a new narrative, built upon his curiousness to understand facts, communicate them, provoke responses and raise new questions.

So really, does your chair talk to you?

Designed objects, just as people, carry the marks of their own history. Details of their descend are often revealed through their personality, age and features. The reasons we relate to them vary from something very personal to something embedded in our culture. Design re-appropriates symbols as pictorial references to awake memories, heritage to provide the ground for rituals and archetypes as a means to reinterpret history in order to make it once more understandable and relevant. The materials give out intimate information on the object’s origin, production process, lifecycle, misfortunes and love stories. Form, ornament and motif are signifiers of specific behavioural patterns that suggest ways of use and provide a safe new pathway through the old and the ordinary. Objects even have names – funny, serious, descriptive, boring or abstract they always add to the elements of their personality – to become more human and trustworthy. With humour and its connotations the designer sparks up the object triggering a giggle, a naughty comment or just a light hearted, cosy and carefree feeling. On the other hand, underlying commentary and metaphors, whether social, political or cultural, can prompt a more critical perspective. These are some of the tools that a designer cannot do without in the process of building his story or making the context more familiar and comfortable. His work always reflects a scenario and comes to life using his capacity to form relationships between matter, space, time & emotion.

The story gives voice to the object and a fascinating dialogue begins. A subliminal exchange of words, memories, images, sounds and chance encounters nurture the formation of a deeper relationship between object and user. The relationship becomes more meaningful in time and the object’s function is second to interacting with it. Since the designer is the one who orchestrates the whole experience, he often chooses to leave room for participation in the development and the end of the story.

As designers at papairlines, we make up stories that not always come to life as objects in a physical sense but also as experiences or even services to observe how they affect everyday life and help interpret one’s surroundings.

We help build connections and create a comfort zone for people to challenge conventions and stereotypes. We welcome on board ideas and people that share our love for exploration and travel. We fly between intangible ideas and tangible applications and as our cabin crew will tell you: we take you places.

OZON RAW International, Shelter, Issue 04, January 2013

Airplanes and Tales

- Categories →

- texts

Portfolio

-

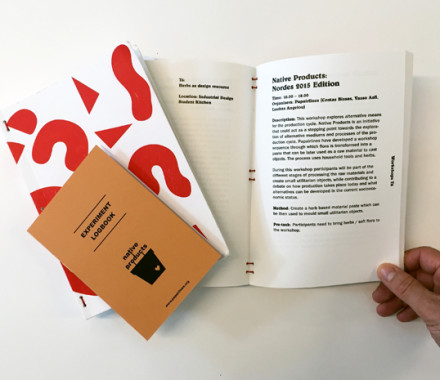

Native Products: The Barbican edition

-

Adhocracy: Athens

-

Nordes 2015

-

Once Upon A Sponge

-

The Good, the Bad & the Irrelevant

-

Once Upon A Sponge: a case study on research through design

-

Multidimensional crisis – multidimensional responses: creative thinking and design as tools for development

-

H&M Denim Art Festival

-

DIY | Who’s the designer?

-

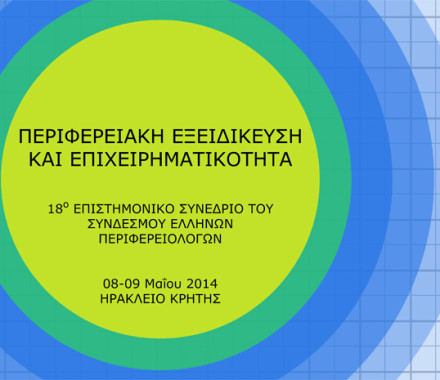

Create vs. Copy/Paste: the contribution of creative thinking in smart specialisation

-

BirdCamp

-

Airplanes and Tales

-

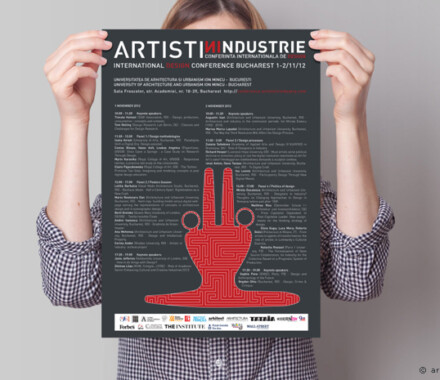

Santorini Biennale of Arts 2012

-

Open Call / DIY: Who’s the Designer?

Clients